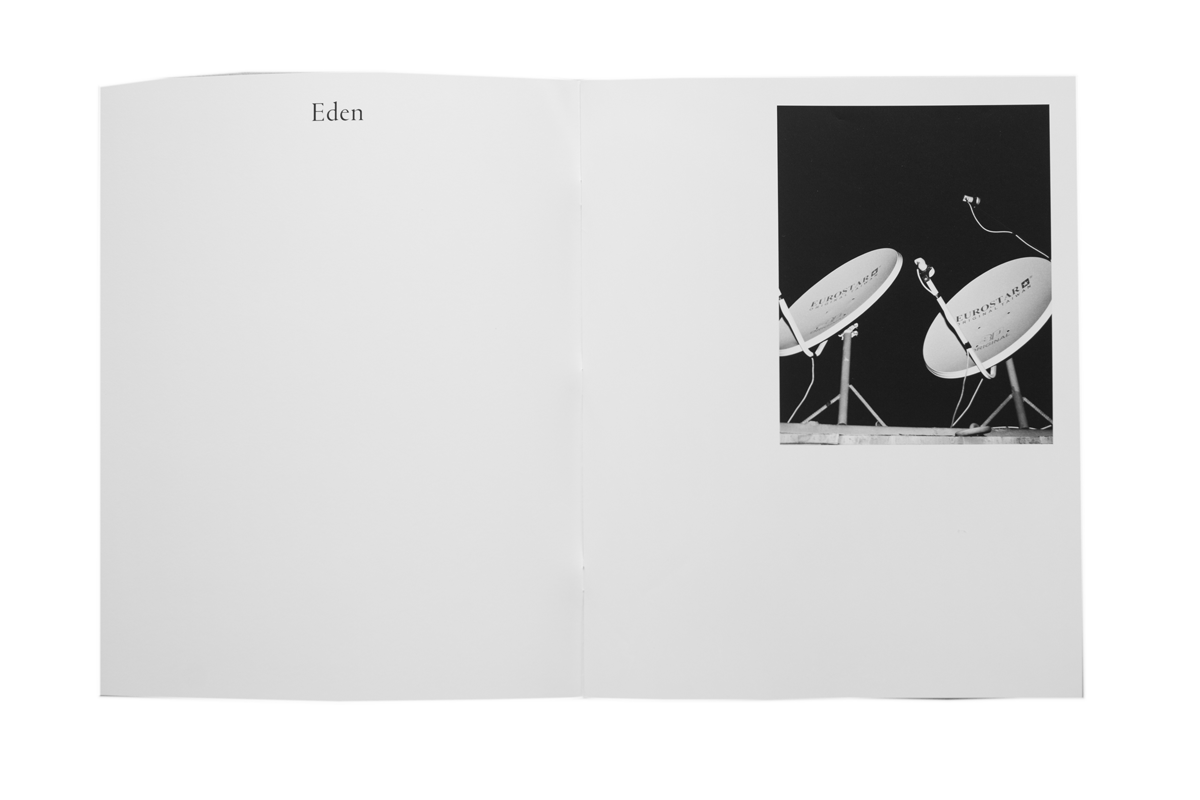

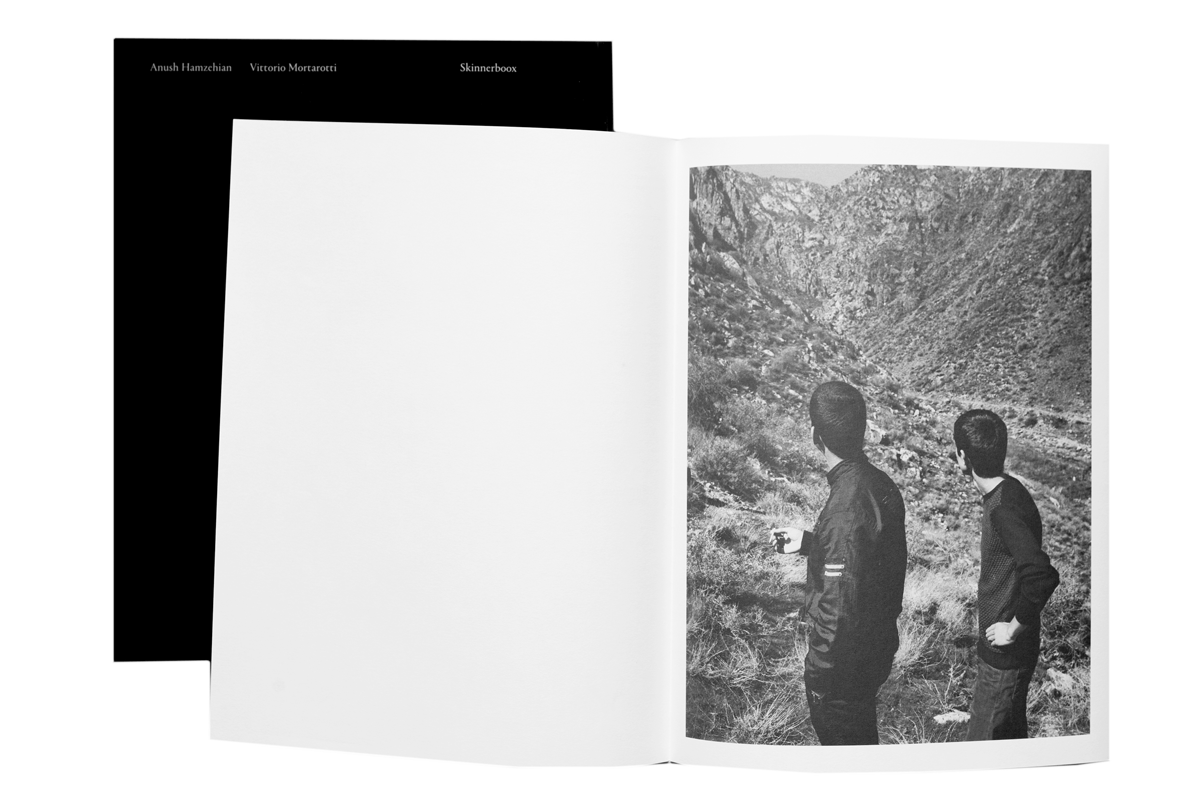

Eden. For many, the biblical notion of paradise symbolizes an imagined place of safety and bliss, only to be fully treasured once one is expelled from it forever. Anush Hamzehian is the son of an Iranian refugee. He was conceived in 1979, the year of the Islamic Revolution, in Tabriz during the last journey his parents took to Iran. As he is not able to travel to Iran, he decided, together with Vittorio Mortarotti, to get the closest they could to the country. In March 2014, they stayed one month in Agarak, a town on the narrow border between Armenia and Iran, investigating the claustrophobia and violence of this border town as a metaphor of all frontiers. On the occasion of the opening of “Eden”, at Fotoraum, Cologne, on January 19, 2018, Richard Sporleder talked to the artists.

Richard Sporleder, Vittorio Mortarotti &

Anush Hamzehian, Foto: Julia Horn für FOTORAUM KÖLN EV

Richard Sporleder: Vittorio, in your first project, „The First Day of Good Weather“, your starting point comes from your personal biography – the loss of your father and brother in a car accident on one side and the aftermath of the Fukushima Tsunami on the other side. What was the autobiographical starting point for „Eden“?

Vittorio Mortarotti: Yes, you are right, these two projects, „The First Day of Good Weather“ and „Eden“ are strongly related. In 2013, I was planning to go to Japan to make „The First Day of Good Weather“ and talked with Anush who has been a friend of mine for a long time, about this project. My purpose was to interweave two stories of loss, apparently so different, and try to investigate the way we all try to go on after a grief. Anush is a film director and he decided to follow me and my story to make a documentary movie which was released in 2015 with the title „Après“.

As soon as we came back we realized that not only we had worked in complete harmony, but that what we did as a duo was much stronger. So we decided to go further with our collaboration and the only way was to make something on Anush’s biography…I mean…somehow I had let him enter deeply in my intimate story and we had to balance it…

Anush is the son of an iranian refugee and he was conceived in Tabriz (Iran) but because of his story he can’t go to Iran and he had never seen the country before. So we chose the nearest point to Tabriz we could reach in order to see the country with our eyes every day. The road that crosses that border goes straight up to Tabriz after a hundred kilometres. But I’d like to stress that in both projects the personal story is a pretext or, as you noticed, a starting point.

Richard: Anush, in „The First Day of Good Weather“ the personal motive disappeared in favor of the general question of how to deal with a loss. Which question came up with “Eden” from the personal experience that the Iranian border, even today, is insurmountable for you?

Anush Hamzehian: Facing a border that we really could not pass has been a very deep and emotional experience. But actually from the very beginning of the project we wanted, as you say, to find a general and universal theme. It was quite easy to realize that we were dealing with a kind of search for a home and so we started to ask people we met why they decided to move or to stay. And also, in order to put a perspective, a future, in their imagination, we asked them to speak about their dreams and particularly to speak about how they imagined the paradise.

The border, the idea of the border, has been changing their imagination. These inhabitants, in this little village in Armenia really think that in paradise they’ll find a sort of border to defend themselves from other people with different origins. The border, this tiny line that we invented, is a powerful instrument of separation. It concerns everybody, in every part of the world.

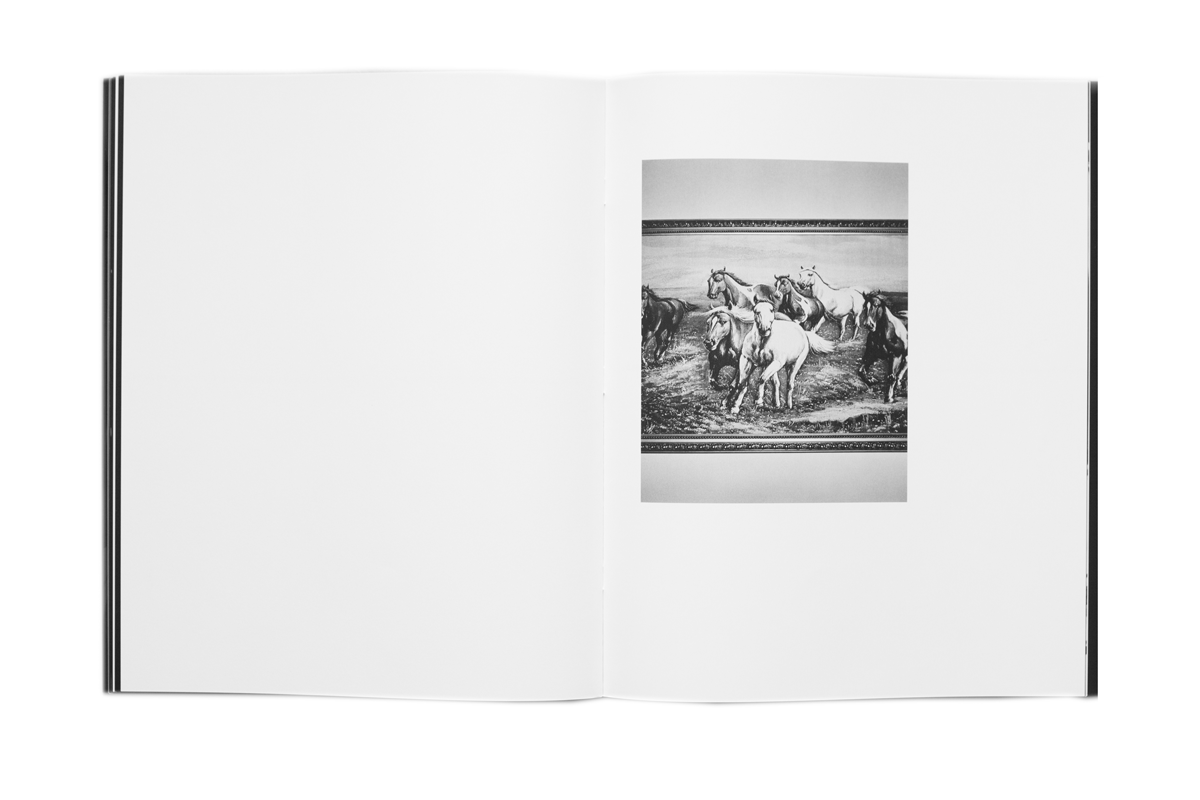

Untitled, from Eden, 2014 – Inkjet print on Hahnemühle PhotoRag Baryta, 141 x 180 cm

Untitled, from Eden, 2014 – Inkjet print on Hahnemühle PhotoRag Baryta, 141 x 180 cm

Richard: Vittorio, did you realize that some Bible researchers actually believe that the paradise from which Adam and Eve were being expelled was in the area around Tabriz? If so, what impact did this have on the project – except for a more complex title?

Vittorio: The title, „Eden“, is an example of the way we like working, on multi-layers. There is an autobiographical reason why this project is called this way: Anush’s mother, telling us about her last trip to Iran with his father (1979), told us that after traveling for one week through Turkey during a military coup, she arrived in Tabriz and it seemed to her to land on Eden. The whole city was in bloom and she could regain the calm she had missed crossing Turkey. We then discovered that for some Bible scholars, the Tabriz area might correspond to the place that inspired the description of Eden. Finally there is a reference to the expulsion from Eden of the „Parents“ for an „original sin“ that the children and the successive generations have to pay for.

There is therefore an autobiographical level, a documentary and a symbolic one, in the choice of the title, but also in the kind of images we make and in the way of setting up and showing the installation.

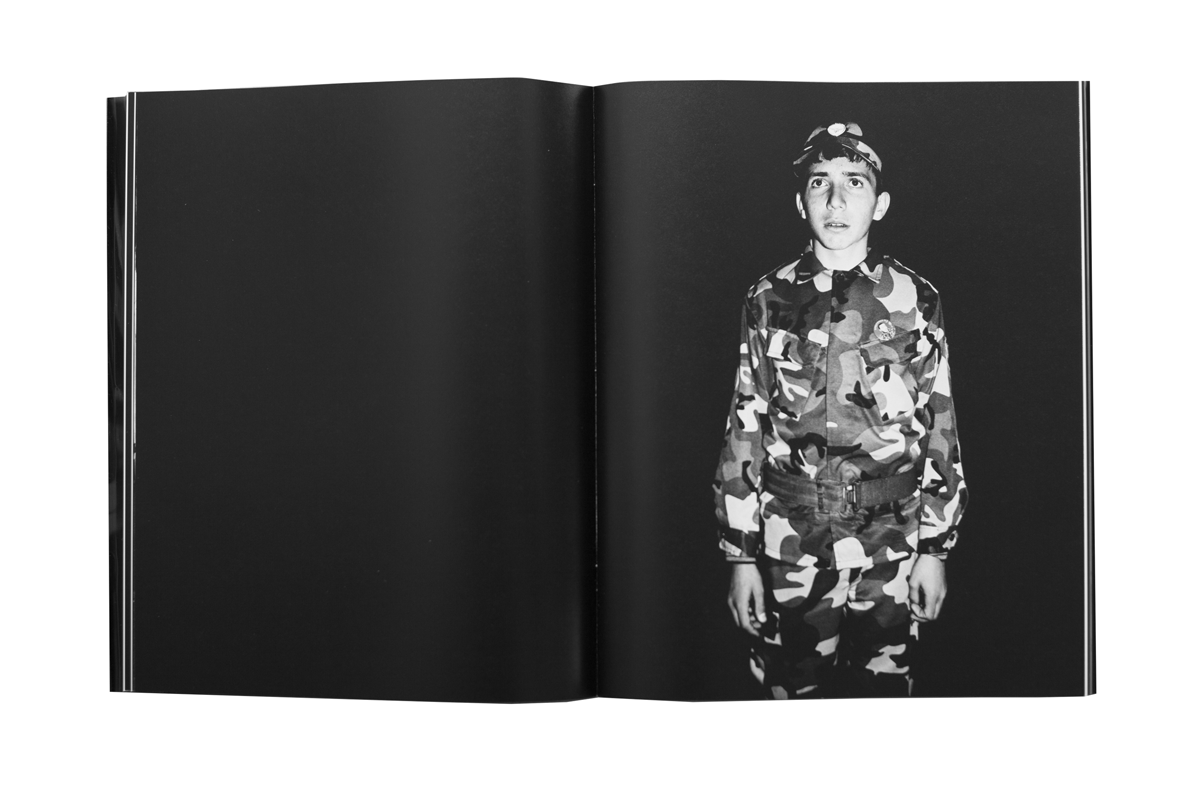

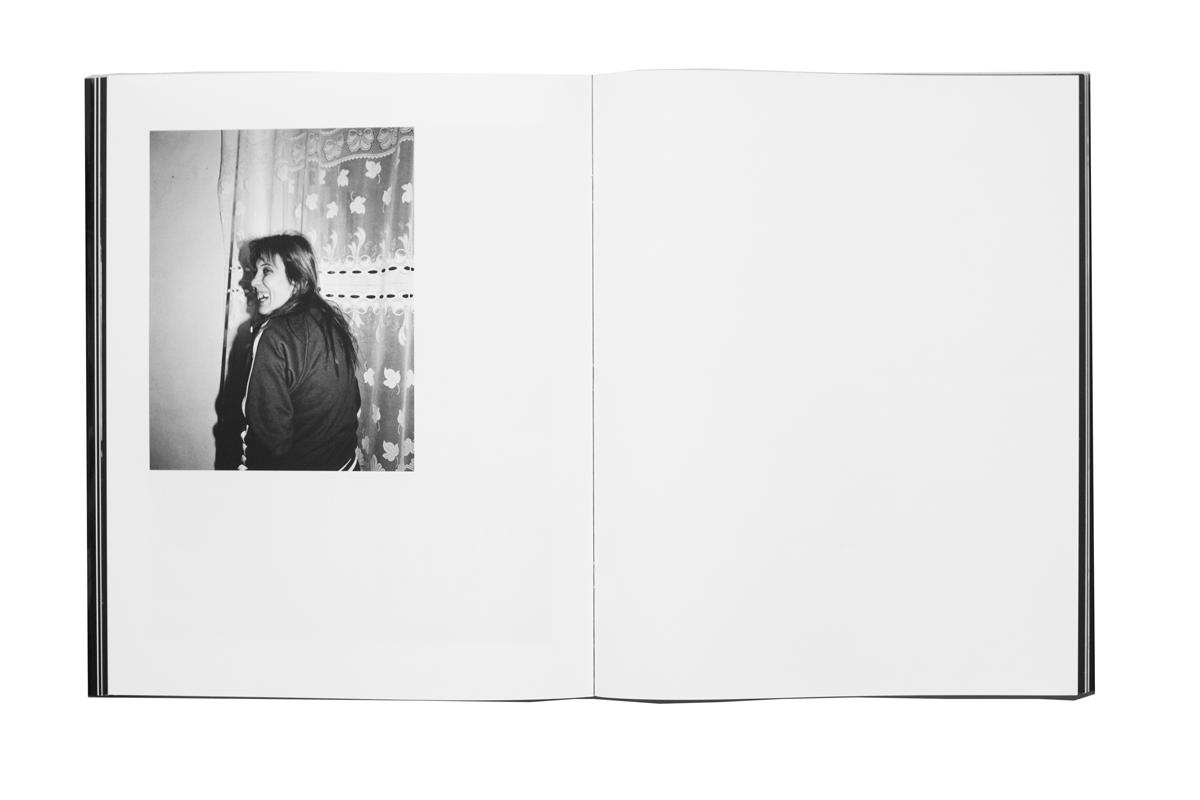

So, the different fates of ordinary people on the border between Armenia and Iran – the young people or the woman who falls in love with a man across the border or the Armenian border guards – reflect, like the title, the complexity of the project.

Untitled, from Eden, 2014 – Inkjet print on Hahnemühle PhotoRag Baryta, 141 x 180 cm

Untitled, from Eden, 2014 – Inkjet print on Hahnemühle PhotoRag Baryta, 141 x 180 cm

Untitled, from Eden, 2014 – Inkjet print on Hahnemühle PhotoRag Baryta, 141 x 180 cm

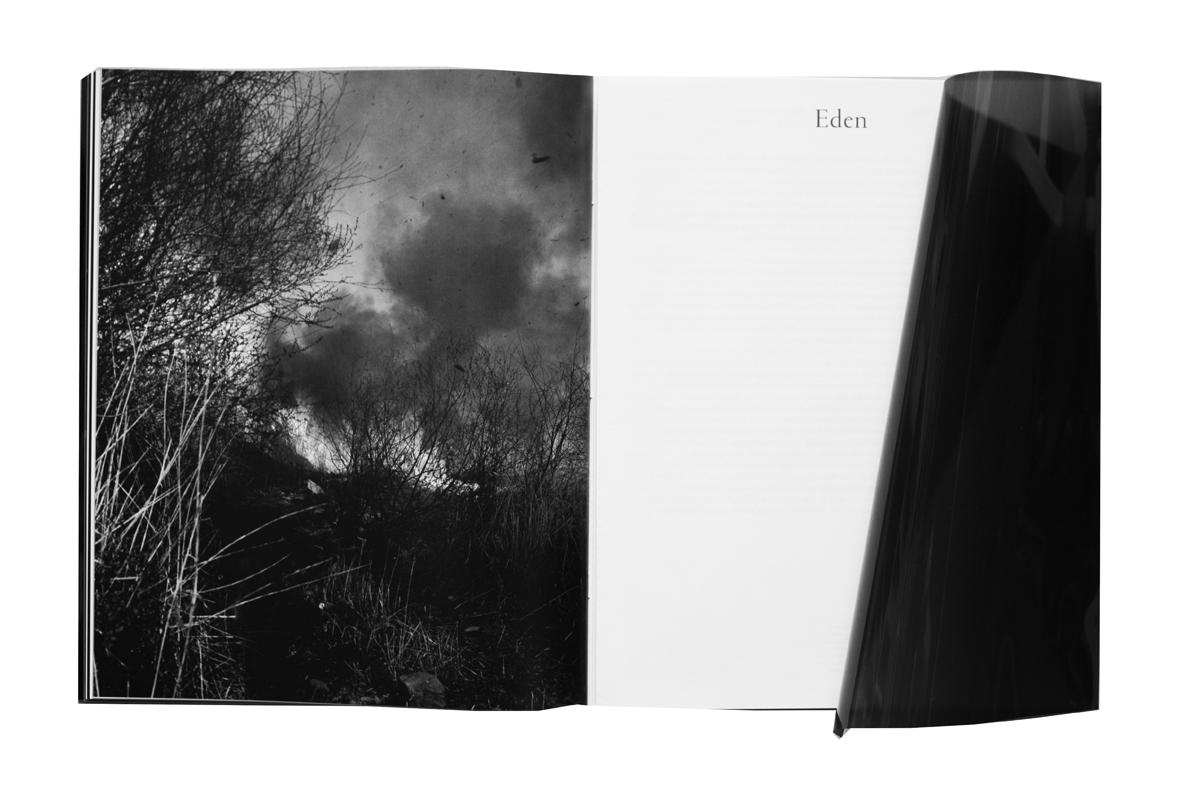

Richard: The absence of colour in your images and the many shots in the blackness of the night seems to give the impression of sorrow and tristess. Was that intended? The video on the other hand is in colour, perhaps you want to make a difference between the media – video, exhibition prints, photo book?

Anush: We wanted, with Eden, to tell the story of a place in which nobody moves, nobody seems to wish a new life or seems to dream about the others, on the other side of the mountains or on the other side of the world. That it is the claustrophobia we felt in Agarak. And so the pictures reflect this feeling. But then we also wanted to give to the audience and also to ourselves some hope, some escaping solution. The video which tells the stories of people dreaming about what they do not know is clearly our intervention, our voice somehow. Meeting a woman who loves somebody on the other side of the border or three teenagers who dream about something different has been very important for us. And it brought some colour to the project, yes.

Richard: When we look at the different portraits of the people in Agarak, I automatically think of the many refugees who came to Germany and are yet to come. If your project is shown here today, what should happen to the viewer when looking at your pictures?

Anush: We always work with some distance from the present. That gives us time, which is a powerful instrument. But of course we live in the present and we see the refugees coming to our countries since some years. Looking at the border between Armenia and Iran for one month without any possibility to cross it, we understood a little more in depth how stupid a border can be. A line, which divides people (as said, a man in Agarak told us that he imagines the paradise with borders in order to separate him from other nationalities). And so we came back from Agarak thinking that it is a human right to cross a border, because the borders are something we invented. We hope, somehow, that the viewer will feel the absurdity of a border as a universal theme.

Richard: Your pictures work on the wall and in the movie. How important is it today, in addition, to publish a photo book and thus go into a financial risk?

Vittorio: We love photobooks and it is as simple as I say it.

We are happy, very happy to work with Milo Montelli of Skinnerboox who believes in our images and our ideas. But it’s up to him to take the financial risk…

Of course, we do spend a lot of energy in making all these different things, but that’s the way we like it…and we do like to take advantage of every medium we use. For example, the exhibition of Eden was conceived to be quite monumental: huge prints, a big video installation…It had to be strong and hard in order to give back the sensation of a border. The book had to find a different narration. It is a kind of journey at the end of the night: it is dark, claustrophobic and it ends with the border on fire.

And let me add something. We are not alone: We had the chance to work with wonderful people like Cécile Martinaud who is the editor of all of our videos and films, Paolo Berra who is the designer of the book, and Stefano Riba who curated the exhibition.

Richard: Like the photo book, it would be nice to have the possibility to see the project (and Show to others, e.g. for educational use) out of the exhibition.

Do you have any plans to make this available, for example as a stream?

Vittorio: The project is on our website (www.hamzehianmortarotti.com) and there you can also find a short teaser of the video, but no, for the moment we are not planning to stream it. The reason is that, as we mentioned before, this project was really conceived as a big installation and we fear that the 3-channel video would lose in strength on a small screen and without the connection with the photographs.

The photobook is the easiest way to see the project wherever you are. So buy the book!

On-artbooks.com thanks the artists & Richard Sporleder of Café Lehmitz Photobooks for the interview.

EDEN, available at Café Lehmitz Photobooks: http://www.cafelehmitz-photobooks.com

Pictures by Anush Hamzehian and Vittorio Mortarotti

Design and layout by Paolo Berra and Vittorio Mortarotti

Published by Skinnerboox on September 2016

First Edition of 500 Copies

Size 26,7 x 33 cm

64 Pages on GardaPat 13 Kiara

6 Pages insert on Fedrigoni Freelife Vellum White

Soft Cover on GardaPat 13 Kiara Black

PVC Cover, ISBN 978-88-941341-6-2

More information about the artists here: http://hamzehianmortarotti.com/

The exhibition „Eden“ is on show at Fotoraum until February 25, 2018.

http://www.fotoraum-koeln.de/